Foggy mornings, Sarus Cranes, Bluebulls, Pelicans, loads of waterfowls and some mesmerising sunrise & sunset scapes is what you associate with Keoladeo National Park at Bharatpur. We at Wild India Eco Tours had one such trip with an amazing bunch of folks to this place in January 2017.

- Tour dates: 13 – 15 January 2017

- Group size: 8

- Total birds species sighted: 115

- Key highlights: Sarus Cranes, Dalmatian & Great White Pelicans, Black & Yellow Bitterns, Black-necked Stork, Dusky Eagle Owl, Oriental & Collared Scops Owls, Red-crested Pochards, Ferruginous Ducks

- Mammals & reptiles sighted: Golden Jackal, Monitor Lizard, Bluebull (Nilgai), Spotted Deer

eBird checklists:

- http://ebird.org/ebird/india/view/checklist/S33634723

- http://ebird.org/ebird/india/view/checklist/S33679213

- http://ebird.org/ebird/india/view/checklist/S33679430

Day 1

Starting from Delhi, we began our journey to Bharatpur by 10:00 hrs after some expected flight delays. We took our 1st halt just after we joined the Yamuna Expressway for a quick snack. A 30 minute break and we were back on our journey. As we neared Mathura, we stopped for our 1st sighting – it was a family of Sarus Cranes!

This was surely some start to the tour as everyone got good views and photographs of this lovely species. Resuming our journey, we arrived at the resort by 14:30 hrs and after a quick lunch and freshening up, we were ready for our 1st excursion to Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary by 16:00 hrs.

Splitting into groups of 2, we began our excursion on the cycle rickshaws. We came across various species of ducks – Common teals, Northern Pintails, Gadwalls, Little Grebes along with numerous Common Moorhens & White-breasted Waterhens. We also got some lovely views of the Oriental Scops Owl – camouflaged perfectly in a tree. Going ahead, we reached an opening were we got to see a pair of Bluebull walking across the wetlands.

Splitting into groups of 2, we began our excursion on the cycle rickshaws. We came across various species of ducks – Common teals, Northern Pintails, Gadwalls, Little Grebes along with numerous Common Moorhens & White-breasted Waterhens. We also got some lovely views of the Oriental Scops Owl – camouflaged perfectly in a tree. Going ahead, we reached an opening were we got to see a pair of Bluebull walking across the wetlands.

We spent rest of the the time at this place itself, watching the beautiful sunset. Some of the birds we saw here were Greylag Geese, Knob-billed Duck, Grey-headed Swamphen, Bronze-winged Jacana and the Bluethroat. While returning back, we were also greeted by a family of Golden Jackals.

We got back to resort by 18:30 hrs for snacks / tea and followed the rest of the evening in introductions, sharing wildlife experiences, making bird list, highlights of the day and finally winding up with dinner.

Day 2

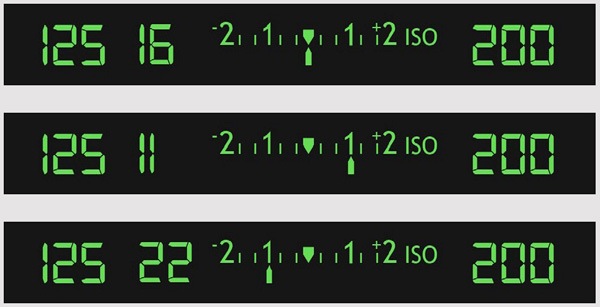

The second day of the tour started as early as 07:00 hrs as we made our entry into the park. The weather was chilly with temperatures around 8 degree celsius. We explored one of the trails were we came across two Great Cormorants perched on a dry branches against the beautiful sunrise – giving us ample opportunities to try out various exposure to make the classic silhouette images. We explored the other side of the trail where we came across waterfowls in big numbers. We also got to see the beautiful Black-necked stork on these trails and a Booted Eagle as well. We returned back to point where we saw the cormorant and this time we saw 5 Spotted Owlets perched close to eachother – indeed a lovely sight.

The weather was chilly with temperatures around 8 degree celsius. We explored one of the trails were we came across two Great Cormorants perched on a dry branches against the beautiful sunrise – giving us ample opportunities to try out various exposure to make the classic silhouette images. We explored the other side of the trail where we came across waterfowls in big numbers. We also got to see the beautiful Black-necked stork on these trails and a Booted Eagle as well. We returned back to point where we saw the cormorant and this time we saw 5 Spotted Owlets perched close to eachother – indeed a lovely sight.

We explored the trees around this place were we saw Red-breasted Flycatcher, Grey-headed Canary Flycatcher and also a pair of Long-tailed Minivets. After spending around an hour, we made our way to the canteen in the park for breakfast. We also got to see a Hume’s Warbler, Lesser Whitethroat, White-cheeked Bulbuls, Shikra and a Golden Jackal crossing the road at this place.

After breakfast, we kept exploring on the main tar road in the park as we came across a variety of species – a Collared Scops Owl pair, a Marsh Harrier busy hunting for a meal, Northern Shoveler, pair of Red-crested Pochards, Bonelli’s Eagle, Oriental Honey Buzzard, Greater Spotted Eagle, White-tailed Lapwings, two pairs of Ferruginous Ducks and numerous Bluethroats, Painted Storks, Great Cormorants, Purple Herons, Grey Herons, Little Grebes, Common Teals and Common Moorhens. Couple of members from our group also got to see and photograph the Great Cormorant hunting and feeding on a huge fish!

As we kept exploring, we sighted the shy Black Bittern in its typical habitat – completely camouflaged in a thick bush. A little ahead we also got to see the Yellow Bittern, this one was bold though as it was busy hunting in the open.

As we kept exploring, we sighted the shy Black Bittern in its typical habitat – completely camouflaged in a thick bush. A little ahead we also got to see the Yellow Bittern, this one was bold though as it was busy hunting in the open.

We did not realise as it was 14:30 hrs already. We proceeded for lunch in the canteen at the park. After lunch, we explored couple of trails near the park were we got decent views of the Dalmatian Pelicans, Cotton Pygmy Goose and a pair Dusky Eagle Owls. We also sighted three types of kingfishers – White-throated, Common and the Pied Kingfisher. After exploring for an hour or so, we made our way back to the sunset point. This time we sighted numerous raptors perched on the trees – Eastern Imperial Eagle, Greater Spotted Eagles (2) and Marsh Harriers. As the light was fading, We also got lucky to sight the shy Black Bitten in open for few seconds before it jumped back into the bush.

Other species seen were a group of Knob-billed Ducks, Grelag and Bar-headed Geese, Black-crowned Night Herons, Grey-headed Swamphens, Oriental Darter and numerous Bronze-winged Jacanas.

Soon the day ended and we were back to resort for yet another experience sharing session, reviewing images followed by dinner.

Day 3

As with Day 2, Day 3 started at 07:00 hrs. The weather was a little more foggy today as we made way into the park. We wanted to take a good chance of sighting the Sarus Cranes and getting better view of the Dalmatian Pelicans in this final morning session and hence we headed straight to the sunset point which has best chance of sightings. We saw couple of Pelicans in flight but couldn’t click them. We started exploring on of the trails a little ahead of the point and soon came across a pair of Sarus Cranes. It was a treat to watch them in the typical Bharatpur scape – standing tall in the long dry grass against bluish foggy background. After getting some decent clicks, we came across similar frames for Oriental Darter, Purple Heron and a Booted Eagle.

As we were returned back to the main road, we saw numerous groups of Great White Pelicans flying to other side of the trail. We went to explore and could see them in good number (over 50 individuals) feeding together. We missed making decent images as it was opposite light. Being content with the sighting, we started back to return to the main tar road in the park when we saw Marsh Harrier flying with a kill and to our luck, it perched right in-front of us and started feeding on its kill..!

Final hour of our session and we had to get back to resort to pack bags start our return journey. We were just exploring for Bitterns again when suddenly a pair of Dalmatian Pelicans came and landed in a water body next to sunset point and began feeding, only to be joined by around 6 more of them. As if a parting gift, we finally got to make some lovely images of this ‘Vulnerable’ species (as per IUCN v3.1). There wouldn’t have been a better end to the trip.

Clearly Keoladeo National Park at Bharatpur stands out as one of the best places to sighting a variety of bird species as well as to learn various aspects of wildlife photography – portraits, landscapes, silhouettes! you get a chance to try them all. Add to it delicious food and an amazing group, we just did not want to return.

That said, we have already planned to visit Bharatpur again in Jan-Feb 2018, this time a 4 Day trip. Stay tuned for the detailed itinerary and exact dates by subscribing to www.wild-india.in.

Thanks for viewing. Let us know in-case of any queries, suggestions, critics and we will be happy to respond.

In-case you have destination & dates in mind, write to us at info@wild-india.in and we shall design custom wildlife tour as per your requirements.

– Team Wild India Eco Tours